The Constitution of Unintended Consequences

The very act of interpreting the constitution, has led to interpretations that pervert its spirit towards tyranny.

Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes?

“If only we could elect politicians that followed the constitution!”

The constant cry for a return to adherence to the constitution from libertarians and conservatives often falls on deaf ears when they cry to us, their anarchist brethren. What does it mean to follow the constitution, when the very mechanism by which the constitution provides in order to police compliance, is itself the problem that has arisen? Every time I hear someone echo their devotion to the constitution, and praise it for what significance it holds in their utopian ethos, I’m reminded of a quote from Lysander Spooner and his work “No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority.”

“But whether the Constitution really be one thing or another, this much is certain - that it has either authorized such a government as we have had or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist.”

― Lysander Spooner, “No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority”

What are we to do, when the very courts and judges charged with enforcing congresses compliance with the constitution and the law, have instead taken it upon themselves, and in fact by their own authority declared themselves empowered to interpret the intent and meaning of the laws, rather than simply enforcing them as written? What are we to do, when the third co-equal branch of government has itself seized the power to not only enforce the law, but to create it, interpret it, and alter it at will?

Many are familiar with Thomas Jefferson’s famous letter to William Smith- yes the one where he praises the occurrence of rebellion within the newly formed United States and makes reference to the Tree of Liberty. But few have bothered to familiarize themselves with the full content of that letter. The context of which was Jefferson responding to having received his first copy of the proposed new Constitution for review while in Paris on the business of the state. In the letter, Jefferson expresses his concerns with some articles of the new constitution, namely the creation of a supreme court, and its tenure.

“There are very good articles in it: and very bad. I do not know which preponderate. What we have lately read in the history of Holland, in the chapter on the Stadtholder, would have sufficed to set me against a Chief magistrate eligible for a long duration, if I had ever been disposed towards one: and what we have always read of the elections of Polish kings should have forever excluded the idea of one continuable for life.”

-Thomas Jefferson, his letter to William Smith, 13 November 1787

During his time in Europe, Jefferson took the opportunity to become studied in the history of the governments that had come and gone on the continent in its long and storied history. What he’d learned, left him opposed to the idea of a supreme court, especially one appointed for life tenure with no oversight or mechanism for easy removal.

I myself am not familiar with the judicial history of Holland that may have led Mr. Jefferson to come to such a conclusion, though my curiosity compels me to become so in the near future. Such reasoning is not explained further in the letter beyond this passage, but the point is clear that there was opposition to the idea of having such a powerful institution as early as 1787. I’ll make no assumption that Jefferson shared the same concerns as anarchists like myself, but I take solace in my stance knowing that the man who drafted the Declaration of Independence was himself opposed to the ideas.

Ostensibly, the courts exist to be the watchers, those who keep the other branches of government in line as part of a delicate series of checks and balances. But now arises the age-old question- quis custodiet ipsos custodes? or, “Who will watch the watchers?” Political Philosopher James Mill believed that the answer to this question lay in the presence of regular elections and a free press, thus expecting the ultimate safeguard against tyranny to be the will of the people themselves or the consent of the governed:

“This has ever been the great problem of Government. The powers of Government are of necessity placed in some hands; they who are intrusted with them have infinite temptations to abuse them, and will never cease abusing them, if they are not prevented. How are they to be prevented? The people must appoint watchmen. But quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Who are to watch the watchmen?—The people themselves. There is no other resource; and without this ultimate safeguard, the ruling Few will be for ever the scourge and oppression of the subject Many.”

-James Mill, The Political Writings of James Mill (1815-1836)

Yet the judiciary of this great nation, the chief magistrate that Jefferson feared, is not elected by the people, but rather appointed by those it is supposed to watch. Furthermore, the Supreme court exists with no further oversight, or action of accountability to the people, with justices appointed for life, and impeachment notoriously difficult and exceedingly rare. This position of impunity would in theory free the justices from the shackles of politics in the exercise of their duties -but are not the very duties of serving the will of the people and upholding the law as they consent to it a political measure?

If it was never intended to be so, it has become so. The judiciary has become inherently politicized. Judges are identified not by their position but by which the president appointed them. Confirmation hearings are focused not on judicial and legal principles, but rather on opinions about the pressing political issues of the day. And judges no longer uphold the law, but rather interpret, enforce, and create it. And they do so with no accountability. Who watches the watchers? Nobody…

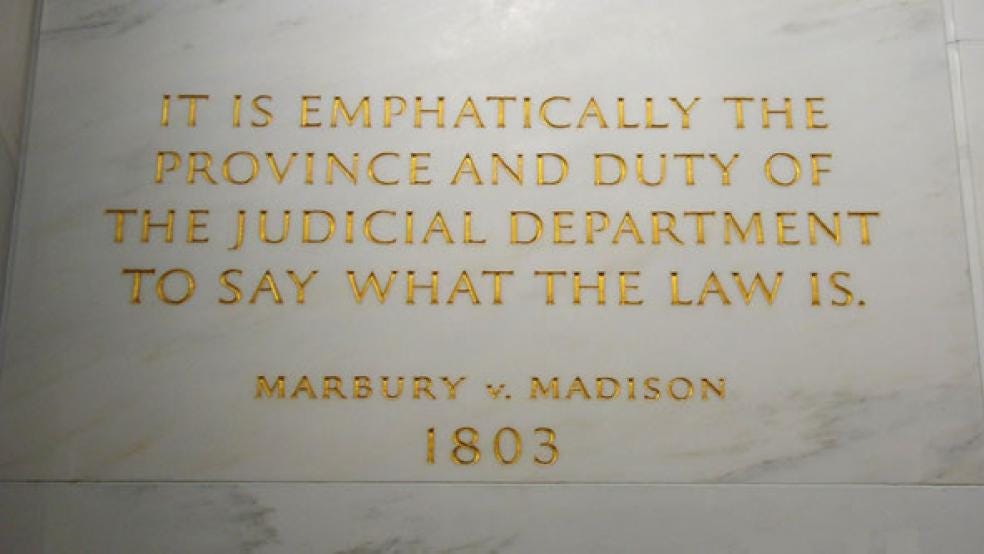

Marbury v. Madison (1803)

The powers of The Supreme Court as we know them today, first became realized at the conclusion of a landmark Supreme Court Decision in 1803, Marbury v. Madison. In an early case of court-packing, President John Adams attempted to pack the judiciary with favorable justices during the lame-duck period of his term as President, after losing his reelection bid to Thomas Jefferson. The appointments were so last minute, that even though they had all been confirmed by the Senate, the secretary of state had not delivered their commissions in time. When Jefferson ordered his secretary of state James Madison to withhold the commission and refuse to deliver them, Willaim Marbury, one of the appointed judges, petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of mandamus ordering Madison to deliver the commissions.

This early in the nation’s history, the Supreme Court was not the political and legal force we know it as today. The institution was still new, and still feeling out its role as a branch of government and establishing the boundaries of its ethics. Chef Justice John Marshall, himself a lame-duck appointment of the Adams administration, and previously the secretary of state charged with issuing the commissions under President Adams, presided over the case regardless of his obvious conflict of interest in its outcome and proceedings.

The questions presented in the case were not simply whether or not Marbury’s constitutional rights had been violated, but whether or not federal law even provided a remedy if they were, and was the Supreme Court even empowered to issue that remedy?

In answering this question, the court necessarily had to establish the limits of its own power. It was this decision, in which The Supreme Court first established that it alone had the power to interpret the law, and overrule an act of congress based on that interpretation.

“[T]he Constitution of the United States confirms and strengthens the principle, supposed to be essential to all written constitutions, that a law repugnant to the constitution is void, and that courts, as well as other departments, are bound by that instrument.”

Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison (1803)

The idea that the Supreme Court was empowered to overrule an act of Congress was not in fact novel, as it was first argued by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers in 1788, but the ruling itself firmly established that principle in law. Just as important, the ruling established the power of the federal courts over other branches of government to interpret the nation’s laws. “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” Marshall wrote. “Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each.” Today, thanks to Marbury v. Madison, the federal courts’ authority is undisputed, and this ruling has been the foundation of The American Judicial System ever since.

Make no mistake, this ruling was a coup. A seizure of power by an unelected, unaccountable judiciary, that declared itself to not be a coequal branch of government, but rather the pinnacle of its power and authority. By claiming the authority to interpret the law, the courts also claimed the ability to craft it to their desire with their decisions.

The 14th Amendment

Ratified on July 9th, 1868, the 14th Amendment was enshrined in conflict and controversy from its very inception. Multiple states withdrew their ratification, even though no process for doing so existed, and President Andrew Johnson was an ardent opponent who actively campaigned against its ratification. Many southern states refused to adopt and ratify it until a Republican-controlled congress issued an edict that any state formerly in rebellion would remain under military occupation and rule until they ratified it. And thus, an amendment requiring the consensus of 3/4 of the states to take effect, was passed with coercion and force, instead of the consent of the governed.

As late as 1957, the very validity of the amendment and the ratification process was contested by some southern politicians and legal scholars. And while this issue has largely been legally settled, and no one today makes any serious claims that the amendment is invalid, every word and possible interpretation of the amendment has been the subject of political and legal controversy ever since.

At 425 words, and 5 distinct sections, it is famously the most complicated of the 27 ratified amendments to the United States Constitution, a jumble of half-understood phrases like “due process,” “privileges and immunities,” “equal protection,” and “shall have engaged in insurrection.” By the very nature of our judicial system, lawyers and legal scholars have been invited forward to offer and propose meanings and interpretations to these and other phrases that suited their ends and their politics. And due to the powers vested in the court by their own decree in Marbury, the courts have been empowered to entertain those suggestions.

From ratification to today, the court’s interpretation has shifted, as the accepted legal definitions of the terms included have changed to accommodate the politics of the justices and the presidents and politicians that appointed them. From Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) allowing racial segregation to remain the law of the land to Brown v. Board of Education (1954) striking down the same statutes 58 years later. And yet, a mere 34 years later, this same amendment was used to justify affirmative action and granting of special privilege based on race yet again in Regents of the University of California v Bakke (1978).

The incorporation doctrine, by which the courts have used the due process clause of the 14th amendment in order to apply the authority of the first ten amendments to the constitution to the states, has been used by the courts to expand their power to define rights not implied explicitly in the constitution. To say this practice has been controversial would be an understatement. Unfortunately, with all the judicial abuses of these powers to call on, the only one most Americans know and care about in today’s political climate is Roe v. Wade (1973) in which the Supreme court found an implied right to medical privacy that when incorporated prohibited the states from outlawing the practice of abortion. I’m pro-choice myself, but recognize that this gross overstepping of authority is a byproduct of two centuries of judicial power-grabbing creating the cultural precedent where decisions like Roe, and now Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Clinic (2022) overturning Roe have become unnecessary flashpoints of political controversy that provide ample evidence that the Judiciary has become too powerful.

The issues alone aren’t rooted solely in the 14th Amendment, or even in the Marbury Case. Article III of the constitution created a judiciary that was capable of becoming the tyrants it was supposed to prevent, and that is the reality of the world we live in today. What is the solution? Abolition? Reform? Resistance? I don’t know, and I don’t pretend to know. But I do hope that we figure it out soon.

Subversive #75: “XIV: How the Fourteenth Amendment Ate the First Ten” with Ian Underwood

Watch on YouTube | Watch on Odysee | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Apple Podcasts

Summary

Many conservatives and libertarians argue that the key to restoring freedom is adhering to the constitution. But how can any document be so perfect, if it has allowed itself to be ignored to such an extent in the first place? Or, has it even been ignored? Was the very passage of the 14th Amendment what did in the need to comply with the first ten? Author Ian Underwood joins the show to talk about the complexity of the 14th Amendment, and his new book “XIV: How the Fourteenth Amendment Ate The First Ten.”

Buy Ian’s book here: https://amzn.to/3P4r0vi

New Merch and Swag!

None other than show sponsor SnekSwag.com has a new full collection of official Subversive Swag where you can show off your rebel side by wearing your principles literally on your sleeves. Check out the collection today to grab your Swag now!

Join the Insurgency!

That’s right, You too can join the insurgency, and help support everything I’m doing here, from the podcast to the newsletter, to real-world activism and legislative lobbying work in New Hampshire.

Join us on Patreon, at Patreon.com/ODonnell for as little as $3 a month to help support the show financially and get some sweet perks as well!

You can also join our community Discord Channel to help grow the community around the show, and chat with other fans at any time! This requires participation, and it will be what we make of it, so join today and let’s grow it from the ground up together!

Copyright Justin O’Donnell, 2022

For Inquiries, contact, and booking: contact@anarchy.email

https://linktr.ee/subversivepod

I'm not sure Brown v Board of Education entirely overturned Plessy v Fergusson. If that had been the goal, the court could have affirmed Harlan's dissent in Plessy instead of relying on evidence of psychological damage done by segregation. And what a different world we would inhabit if they had done so. As Harlan wrote, "But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." Indeed, a much simpler approach to adjudicating disputes among free people.

He also wrote, "In respect of civil rights, common to all citizens, the constitution of the United States does not, I think, permit any public authority to know the race of those entitled to be protected in the enjoyment of such rights. Every true man has pride of race, and under appropriate circumstances, when the rights of others, his equals before the law, are not to be affected, it is his privilege to express such pride and to take such action based upon it as to him seems proper." This recognizes the incendiary notion of white pride, a concept anathema to modern-day champions of the Brown decision, along with what South Africa is referred to as "Positive Discrimination" and what we in the US know as "Affirmative Action."